Immigrants have a unique history of service in the U.S. military. By looking at the ways in which they have kept Americans safe and benefitted our country as service members, perhaps we can find solutions to problems the military faces today. For instance, the Army fell 15,000 soldiers short of its recruitment goal in 2022 in what leadership is calling “the war for talent.” Historically, foreign-born service members have made vital contributions to the military, filling desperately needed roles as highly skilled translators. In the face of struggles across the board with the U.S. labor force, the military could once again rely on immigrants to fill those boots that provide us with an invaluable service.

If they played a larger role in the military, immigrants would continue to demonstrate bravery, selflessness and civic duty. A disproportionately high share of the immigrant population, four percent, have enlisted in the military after a rigorous vetting process. After completing their service, they continue to pay it forward to society as veterans.

Historical Contributions

Over the last 100 years, more than 760,000 noncitizens have enlisted and gained U.S. citizenship, with more than 158,000 doing so in the last 20 years. Examples of foreign-born military heroes go back even further.

During the Revolutionary War, Prussian American volunteer Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben whipped the Continental Army into shape as the Inspector General appointed by George Washington, while volunteers like English American essayist Thomas Paine built a revolutionary spirit with rousing pamphlets. During the Civil War, immigrants and their sons made up more than 40 percent of the Union Army and were instrumental in the Union victory against the Confederate Army and institutional slavery. For more information on immigrants’ accomplishments throughout history, we encourage you to consult our Teaching U.S. Immigration Resources catalog.

The tendency of foreign-born Americans to excel in military service has continued throughout modern American history. One need look no further than the examples of World War II veteran Pedro Cano and Vietnam War veteran Jesus S. Duran, who were awarded posthumous Medals of Honor by President Obama. The only justifications for their not having received it earlier were their ethnicities and backgrounds as immigrants. Despite this history of discrimination, foreign-born Americans account for 20 percent of all Medal of Honor recipients. These sacrifices for national security and their fellow countrymen have carried through to this day.

The fact that immigrants speak languages other than English and have experience with other cultures have made them very important in overseas operations such as the Iraq War, when Farsi and Arabic speakers helped ease tensions between the military and local civilians. These linguistic and cultural skills are highly sought after and are exceedingly difficult to cultivate without foreign-born service members.

The knowledge and expertise that immigrants bring to the military on a technical level should not be understated either. Hedy Lamarr, a well-known actress, was behind innovations in communications technologies that military GPS still relies on today. Immigrants also played a part in the invention of submarines, helicopters and ironclad ships. These technologies have been a central part of the U.S. military’s success on the world stage.

Immigrants in the Military Today

As mentioned earlier, the U.S. military is experiencing recruitment shortfalls across the board, which might ultimately result in 12,000 positions being cut. Immigrants could be a part of filling this gap, as they are already valuable members of the military.

As mentioned earlier, the U.S. military is experiencing recruitment shortfalls across the board, which might ultimately result in 12,000 positions being cut. Immigrants could be a part of filling this gap, as they are already valuable members of the military.

There are an estimated 45,000 immigrants actively serving in the U.S. military, which requires them to be permanent legal residents and can offer a path to citizenship. Around 5,000 permanent residents enlist each year, though fewer immigrants have gained citizenship through military service in recent years. This comes as a direct consequence of government policy requiring mandatory wait times for citizenship paperwork.

Looking at service records also highlights the contributions of immigrants to the military. As an example, noncitizen recruits were found to stay in military service longer than average as a result of low attrition rates. On average, four percent of noncitizens leave service after three months, 16 percent after three years and 18 percent after four years. These figures are lower than the military-wide average.

Immigrant servicemembers also excel academically. They are more likely to be college graduates and less likely to be high school dropouts. Immigrant veterans have higher rates of educational attainment than non-veteran immigrants, gaining knowledge to apply to high-skilled work upon completing their service.

The U.S. government has enacted immigrant recruitment programs before, and these programs have proven to be effective ways to attract new recruits. Most recently, the Army undertook a program aimed at attracting language and medical specialists. They did so by offering immigrants the opportunity for a fast track to citizenship.

Immigrants have contributed a great deal throughout our history and will remain a vital part of our collective safety, but the life of a servicemember does not end when they are discharged, and the contributions of immigrant veterans are also worth considering.

Immigrant Veterans

It should be said first that veterans as a group are exceptional individuals. Not only do they serve their country during their prime working years, but they also go above and beyond non-veterans in public service, education, entrepreneurship and civic participation. Veterans are more likely to serve in state legislatures, more likely to vote, more likely to obtain all types of degrees and save businesses money due to tax incentives.

It should be said first that veterans as a group are exceptional individuals. Not only do they serve their country during their prime working years, but they also go above and beyond non-veterans in public service, education, entrepreneurship and civic participation. Veterans are more likely to serve in state legislatures, more likely to vote, more likely to obtain all types of degrees and save businesses money due to tax incentives.

There are currently 530,000 immigrant veterans, and the majority, 83 percent, are naturalized U.S. citizens. Foreign-born veterans speak English at higher levels than foreign-born non-veterans, and immigrant veterans participate in the civilian labor force at higher-than-average rates, with 58 percent of veterans working in essential sectors of the economy.

Despite evidence pointing to the fact that immigrants diligently serve in the military and make positive contributions to society upon leaving military service, there are laws in place that make it easier for them to be deported, namely the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. Estimates vary, but data show that at least 94,000 veterans have been deported because of this law, which gives fewer opportunities to those who have made the U.S. safer. Take the case of Manuel and Valente Valenzuela, two brothers who fought in the Vietnam War. Decades after completing their service, they were deported for minor misdemeanors committed long ago. Since the 1996 bill was passed, veterans have been deported for misdemeanors such as disorderly conduct.

These stories all show that immigrants are a vital part of a strong and capable U.S. military. They make extraordinary efforts to save human lives and build their communities. Their contributions speak for themselves, and they should be treated with respect and human decency. The problems that immigrant veterans and servicemembers face, such as discrimination against translators, show that their contributions are undervalued and hidden from view. We should shine a light on these American heroes.

The $6.7 billion Florida citrus industry owes a lot to Lue Gim Gong’s mother. She taught her son pollination techniques while raising him in China. As an adult in the United States, he would use those techniques to breed so many valuable new varieties of fruits that he gained the nickname the “Citrus Wizard.”

The $6.7 billion Florida citrus industry owes a lot to Lue Gim Gong’s mother. She taught her son pollination techniques while raising him in China. As an adult in the United States, he would use those techniques to breed so many valuable new varieties of fruits that he gained the nickname the “Citrus Wizard.”

Hanukkah, also known as the Festival of Lights, is an ancient Jewish holiday that commemorates the rededication of a Temple in Jerusalem after winning it back from the Greek occupiers in the second century BCE. Historically Hanukkah had been considered a minor event in the Hebrew calendar, but

Hanukkah, also known as the Festival of Lights, is an ancient Jewish holiday that commemorates the rededication of a Temple in Jerusalem after winning it back from the Greek occupiers in the second century BCE. Historically Hanukkah had been considered a minor event in the Hebrew calendar, but  Joel Roberts Poinsett may have been an American diplomat and amateur botanist, but the “flor de la

Joel Roberts Poinsett may have been an American diplomat and amateur botanist, but the “flor de la

The dawn of each new year is celebrated across the globe. Perhaps the most famous observance, the annual Times Square Ball Drop in New York City, was created by an immigrant. Prior to 1904, New Yorkers celebrated New Year’s Eve with

The dawn of each new year is celebrated across the globe. Perhaps the most famous observance, the annual Times Square Ball Drop in New York City, was created by an immigrant. Prior to 1904, New Yorkers celebrated New Year’s Eve with  The story of the Easter Bunny was brought to the United States by German immigrants. The mythical bunny known as an “

The story of the Easter Bunny was brought to the United States by German immigrants. The mythical bunny known as an “

Early Protestant immigrants to the United States didn’t approve of the holiday’s mischief-making or pagan connections. It wasn’t until waves of Irish immigrants arrived in the 19

Early Protestant immigrants to the United States didn’t approve of the holiday’s mischief-making or pagan connections. It wasn’t until waves of Irish immigrants arrived in the 19

The path to legal equality has been even slower and bumpier for transgender immigrants than for gay, lesbian and bisexual immigrants. The government’s evolving understanding of gender identity and how it relates to sexual orientation has led to some confusing, inconsistent policies. In the landmark 2000 case

The path to legal equality has been even slower and bumpier for transgender immigrants than for gay, lesbian and bisexual immigrants. The government’s evolving understanding of gender identity and how it relates to sexual orientation has led to some confusing, inconsistent policies. In the landmark 2000 case

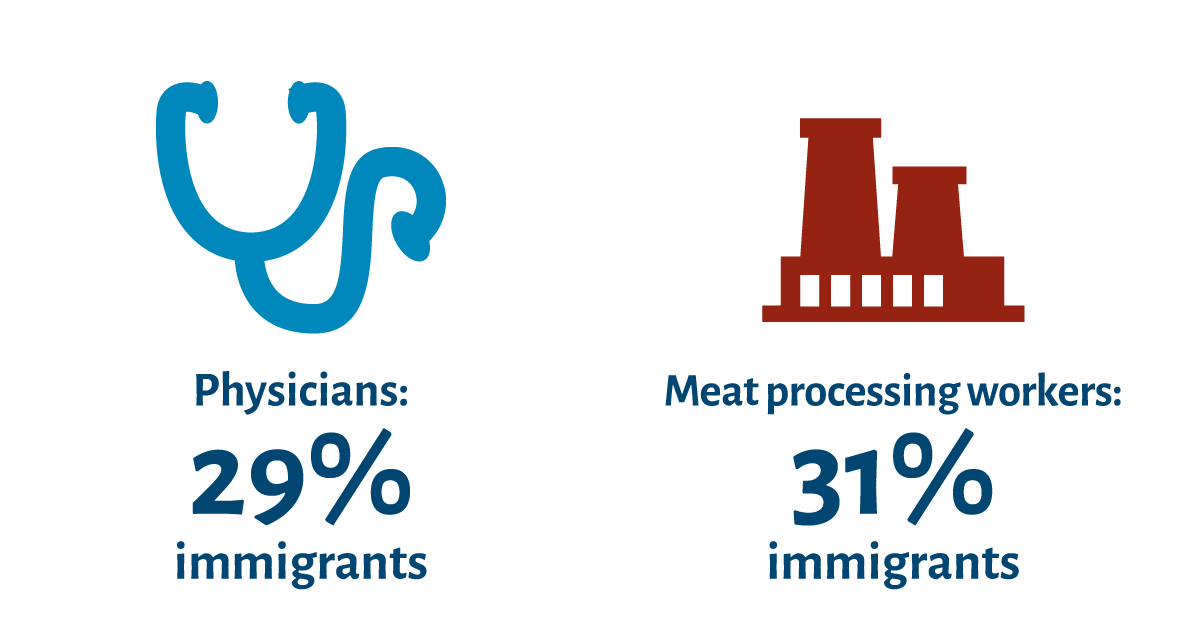

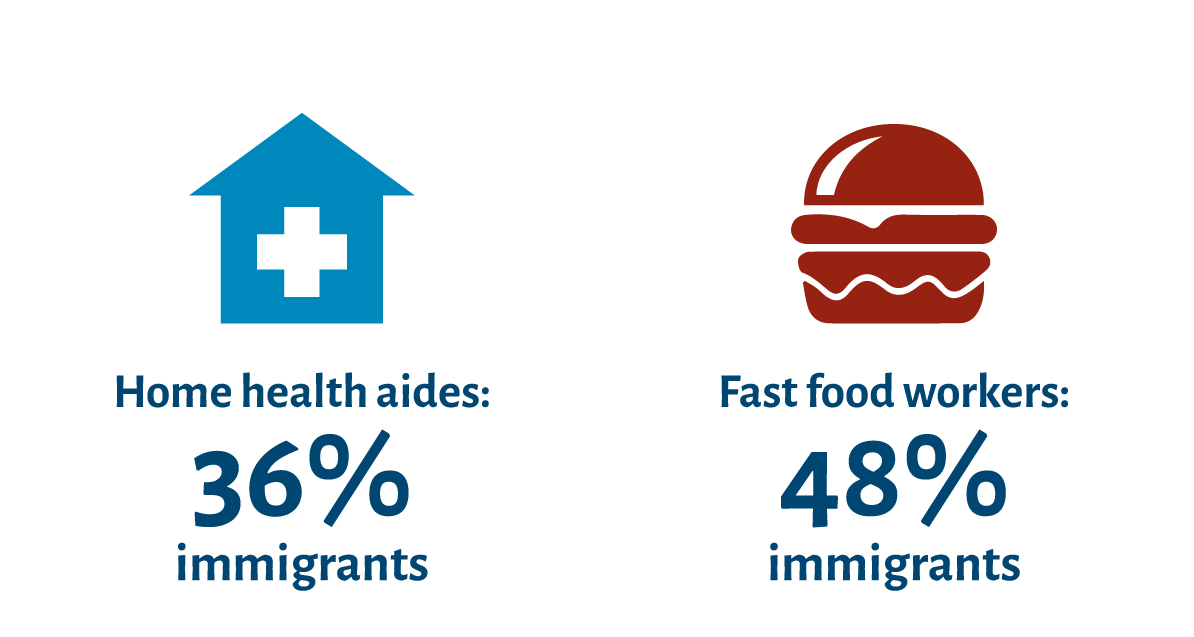

Immigrant essential workers’ contributions during the COVID-19 crisis have been crucial and oversized. Foreign-born people make up just 14 percent of the U.S. population but 18 percent of the essential workforce. While 65 percent of U.S.-born workers are essential workers, 69 percent of all immigrants in the U.S. labor force and 74 percent of undocumented workers are essential. To name just a few essential occupations, 36 percent of home health aides, 29 percent of physicians, 31 percent of meat processing workers and 48 percent of fast-food workers are immigrants. Despite the often dangerous conditions, our report shows that foreign-born frontline workers have remained committed to supporting their communities through the pandemic. As one interviewee working in health care reflected, “I didn’t think that quitting was a

Immigrant essential workers’ contributions during the COVID-19 crisis have been crucial and oversized. Foreign-born people make up just 14 percent of the U.S. population but 18 percent of the essential workforce. While 65 percent of U.S.-born workers are essential workers, 69 percent of all immigrants in the U.S. labor force and 74 percent of undocumented workers are essential. To name just a few essential occupations, 36 percent of home health aides, 29 percent of physicians, 31 percent of meat processing workers and 48 percent of fast-food workers are immigrants. Despite the often dangerous conditions, our report shows that foreign-born frontline workers have remained committed to supporting their communities through the pandemic. As one interviewee working in health care reflected, “I didn’t think that quitting was a

R

R

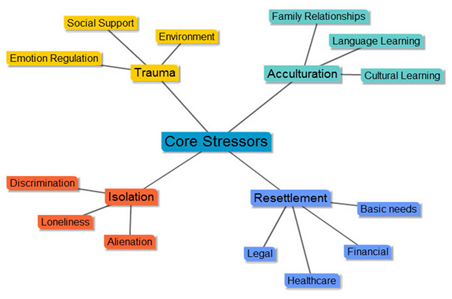

Trauma is very common among unaccompanied minors. Being separated from their families itself is a form of trauma. Trauma responses often surface after students have resettled, when the immediate stress and danger of their journey has ended. Our

Trauma is very common among unaccompanied minors. Being separated from their families itself is a form of trauma. Trauma responses often surface after students have resettled, when the immediate stress and danger of their journey has ended. Our  By definition, unaccompanied minors have spent time separated not just from their community but also their family. Some unaccompanied minors have long journeys to the United States that conclude with being shuffled around multiple shelters with

By definition, unaccompanied minors have spent time separated not just from their community but also their family. Some unaccompanied minors have long journeys to the United States that conclude with being shuffled around multiple shelters with