Rates of unaccompanied minors crossing the border have been rising significantly, and so are the chances an unaccompanied minor will join your classroom. These young people have strengths, challenges and needs that are distinct from immigrant children as a whole. They are being housed in households across the country, so it’s worthwhile to prepare to welcome an unaccompanied minor wherever you are located.

Rates of unaccompanied minors crossing the border have been rising significantly, and so are the chances an unaccompanied minor will join your classroom. These young people have strengths, challenges and needs that are distinct from immigrant children as a whole. They are being housed in households across the country, so it’s worthwhile to prepare to welcome an unaccompanied minor wherever you are located.

For more tools to teach unaccompanied minors, explore our comprehensive, searchable Teaching Refugee, Unaccompanied Minor and SLIFE Students resource page.

Where they come from and where they are going

While almost all unaccompanied minors cross the southern border, not all are Latinx. They are typically teenagers who speak little to no English and may not even speak Spanish. Youth from indigenous communities in South and Central America may exclusively speak one of 560 indigenous languages, making it hard or impossible to access a translator in the immigration system. Once apprehended at the border, unaccompanied children are usually held in detention facilities. They have the legal right to learn while in long-term detention, but facilities generally provide inadequate education and care. This may not be the first interruption to their education. If they are fleeing war, unrest, poverty, gangs, a natural disaster and/or other traumatic conditions in their country of origin, they might have attended school irregularly or dropped out of school altogether.

When minors are released from detention, they are put in the care of temporary caregivers, who are more likely to be family members than unrelated foster parents. These caregivers can be located anywhere in the country, so it’s not just teachers working along the U.S. southern border who might be receiving them into their classrooms. You can see how many minors have been placed with sponsors in your county between October 1, 2020 and August 31, 2021 here and in previous years here. Unaccompanied minors are also simultaneously placed into deportation court proceedings. It is possible, therefore, that they won’t be your student for a long time, but this doesn’t mean that they can’t be educated and supported while in your classroom.

Focus on Strengths

Recognizing the unique strengths and resiliencies of unaccompanied minor students helps build their confidence and abilities. Unaccompanied minors come with talents and contributions to offer. Many are, or quickly become, multilingual and multicultural. They are often more independent and likely to have more life experience than their fellow students. Studies have found that immigrant and refugee students in general are a benefit to their classrooms. Immigrant students bring diverse perspectives to their schooling. Recognizing, acknowledging and celebrating the strengths of unaccompanied minors can help immensely in mitigating their stressors.

Recognizing the unique strengths and resiliencies of unaccompanied minor students helps build their confidence and abilities. Unaccompanied minors come with talents and contributions to offer. Many are, or quickly become, multilingual and multicultural. They are often more independent and likely to have more life experience than their fellow students. Studies have found that immigrant and refugee students in general are a benefit to their classrooms. Immigrant students bring diverse perspectives to their schooling. Recognizing, acknowledging and celebrating the strengths of unaccompanied minors can help immensely in mitigating their stressors.

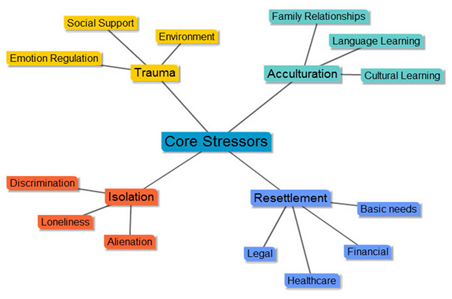

Core Stressors Model

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital Trauma and Community Resilience Center have developed a “core-stressors” model that can help educators understand and support unaccompanied minors. The model identifies four central stressors facing unaccompanied minors and offers strategies for addressing them. These four stressors are acculturation, resettlement, trauma and isolation. All these challenges have been exacerbated by COVID-19. This article will describe the model, section by section, to explore how teachers can address the needs of unaccompanied immigrant and refugee minors in classrooms. To apply the model in more depth, you can explore the accompanying toolkit created to guide teachers through supporting their students.

Dr. Jeffrey Winer describes the four elements of the core stressor model.

Core Stressor: Acculturation

Acculturation is the process of adapting to a new culture. There is more information on the topic in this blog post on immigrant trauma. Unaccompanied minors may face more challenges in their acculturation process than other immigrant students. They are often coming from detention centers where they were very isolated from the rest of the United States, limiting their options for exploring and adopting new cultural practices. They may not speak any English and may be unable to communicate with those around them, especially if they are placed with a foster family.

Immigrant families move from being ‘cultural survivors’ to ‘cultural leaders.’ Learn more in our blog post Engage Families to Support Immigrant Students.

Placements with both biological families and foster families carry challenges and benefits. Biological families may have their own complicated relationship with acculturation. Immigrant parents sometimes feel their child is becoming “too American,” too quickly. If the unaccompanied minor students are new arrivals and their sponsor family has become more “Americanized” while in the United States, the opposite may occur. Foster families may not understand an immigrant’s culture or country of origin. Students may also experience cultural conflicts or misunderstandings with peers. While teachers cannot resolve all the acculturation challenges facing their students, they are well situated to help.

You can reduce the “othering” of your students by setting clear classroom guidelines for both foreign-born and U.S.-born students. Creating ground rules for respectful conduct and language will make your expectations of your students clear, and make it easier to hold students accountable if they say something inappropriate. Give opportunities for students to share their own cultures in a positive context. Hosting an “International Day,” organizing a show-and-tell where students share an object that represents their families, and similar activities are ways to make students the “teacher” of their backgrounds.

It’s vital to provide openings for students to share their unique experiences without singling them out and making them feel “othered.” All students have interesting cultural backgrounds to share, not just unaccompanied minors in the process of acculturation, so there are benefits to encouraging all students to embrace and share their backgrounds. As will be discussed in the section on trauma, pressuring students to share their stories may trigger unpleasant or even harmful memories. Students should be given opportunities, not mandates, to speak up. Let your students acculturate to the degree they desire and at the pace they choose. For example, avoid giving your students anglicized nicknames. Names can carry tremendous cultural or familial significance, and teachers shouldn’t try to “improve” them on their students’ behalf. By the same token, don’t discourage your students from adopting conventionally American names if they choose to do so. Allow unaccompanied minors to decide how much they want to change as they adapt to their new community.

It’s not uncommon for educators to feel anxious or insecure if there’s a cultural divide between them and their students that they don’t know how to bridge. Fortunately, there are effective ways to overcome those divides. If there is a substantial local community of people who share your students’ cultures, teachers can improve their own cultural understanding by engaging with it openly and fully. Attending local cultural events can help improve your cultural fluency. Learning to speak the native language of your students, even conversationally, is a tough but highly effective way to make them feel welcome. Even learning a few simple phrases can demonstrate to students that you’re invested in engaging with them.

Core Stressor: Resettlement

Unaccompanied minors can face significant struggles with the resettlement process, which includes accessing basic resources like medical care, including mental health care, affordable housing, and legal and financial assistance. Their families might not be equipped to connect unaccompanied minors with the resources they need, particularly if they are the child’s biological family and struggling with resettlement themselves.

Unaccompanied children and their families are often low-income. Minors may be expected to work, help pay rent and even send money to family in home countries. This can interfere with their ability to thrive in or even attend school. Financial and language barriers can also make it harder to access resources in their community. Their legal status might bar them from some forms of government assistance. Poverty and immigration status can create challenges that overlap and compound each other. An inability to afford or access medical care or legal services is especially dangerous for immigrants who are more likely to have unaddressed physical and mental health needs, and often desperately need legal help.

Educators cannot meet all of their students’ needs, but they can help connect them to organizations that might be able to assist. Unaccompanied minors are generally not entitled to legal assistance, but there may be free or low-cost legal resources available in your community. This is especially important since unaccompanied minors are far more likely to win their deportation cases when they have legal representation. Connecting students with cultural organizations can help them integrate into their communities, something explored further in the section on isolation. Many not-for-profits offer legal, financial and medical assistance to immigrant and refugee families, but families must know that they exist in order to take advantage of them. With a little research, you can bridge the gap between your students and helpful organizations and resources in your area. Here is a list of organizations supporting unaccompanied immigrant children across the country that could get you started.

There are also a number of ways that school systems are legally obligated to support unaccompanied minor students. Teachers may need to research their students’ rights to ensure they’re being met. Schools must enroll unaccompanied minors promptly, have English language learners assessed quickly and provide materials in home languages, among other responsibilities. A more comprehensive list of unaccompanied children’s rights is available here. Unaccompanied minors also have the right to be placed into mainstream classes as much as possible, not funneled into adult education programs. Know-Your-Rights trainings are helpful for both students and teachers who may not know about the resources the students are entitled to.

Engaging families, particularly if the unaccompanied minor has been reunited with their biological family, can also help students’ resettlement processes. If parents grow more confident and capable of engaging with their children’s school, the student will receive more support. Our blog post Engage Families to Support Immigrant Students details how to reach out to immigrant parents and involve them in their student’s academic success.

Laura Gardner describes the four stages of immigrant parents’ involvement in their children’s education.

Core Stressor: Trauma

Trauma is very common among unaccompanied minors. Being separated from their families itself is a form of trauma. Trauma responses often surface after students have resettled, when the immediate stress and danger of their journey has ended. Our blog post on immigrant trauma goes into depth on the topic. Pre-migration, migration and resettlement trauma could all be present. Students may be fleeing oppression, war, gangs or extreme poverty. Rates of sexual assault, abduction, trafficking and other forms of violence are very high on journeys to the U.S. Rates of abuse and neglect can be high in immigrant detention facilities in the U.S. as well.

Trauma may show up as hyperactivity, truancy, withdrawal, mood swings, irritability and other “problem” behaviors. Responding with empathy and support rather than punishment is vital. One simple strategy to help students process their experiences is to encourage them to write, talk or even create art about their stories. It’s important to make sure these activities are voluntary. Pushing students to relate or relive painful experiences can cause trauma to resurface in harmful ways.

Some ways to address trauma in unaccompanied minors can also help address other stressors, like resettlement and isolation. You can research mental health resources available to students, both in and out of school. Connecting students, and potentially their families, to these resources can close the gap between them and the mental health care that they need. For example, without orientation, foreign-born students may not understand how a school guidance counselor can help them.

Preventing or ending isolation, which is addressed further in the section on isolation below, can also ease the effects of trauma. Creating strong connections with peers and with the school itself can improve students’ mental health. General trauma-informed teaching principles also apply to unaccompanied minors. This resource has detailed suggestions for trauma-informed teaching practices. Some strategies include offering students as much autonomy as possible, setting predictable schedules, engaging with students outside of academics, and giving students opportunities to demonstrate competencies and strengths. It benefits all students to approach them with an open, empathetic mind and stay attuned to signs that they are in distress.

Using cultural sensitivity when addressing trauma is vital. One simple way to be more culturally sensitive when supporting students is to ask students, “What do you do at home that makes you feel better?” Let their answer guide how you express support. Using family liaisons can help you connect with students and families on comfortable ground, making it easier to raise concerns around trauma and mental health.

Experts discuss strategies for tackling immigrant and refugee trauma.

Core Stressor: Isolation

By definition, unaccompanied minors have spent time separated not just from their community but also their family. Some unaccompanied minors have long journeys to the United States that conclude with being shuffled around multiple shelters with high turnover rates among residents, leaving them cut off from any sense of community for a long time. This is particularly concerning because research shows that lack of family or community support is a high-risk factor for mental health problems for immigrant and refugee children. On the other hand, close family ties and social support from peers help protect students from mental health problems.

Feelings of isolation may persist for unaccompanied minors even if they’ve been reconnected with biological family. It can be hard to rejoin a family after a long separation, particularly amid traumatic and stressful circumstances. Family members who have been separated for a long period of time may struggle to adjust to living with relatives who have grown older and changed during their absence. Unaccompanied minors may have new stepfamilies or younger siblings, which can lead to intra-family conflict. If unaccompanied minors are placed with a host family, they may not know anyone who speaks their native language or understands their culture. Unaccompanied minors are often more independent than average, setting them up for conflicts with caregivers with different expectations of minors’ autonomy. Your students might face bullying and discrimination, both in and out of school, which will prevent them from feeling meaningfully engaged with their new community.

As a teacher, you are best situated to help your students feel connected to their classmates and their school community. One strategy is to create a buddy system with other students, ideally pairing newly arrived unaccompanied minors with multilingual students. You can also organize activities like clubs, lunch groups and other social opportunities that encourage interpersonal connections. If your school has a large group of students who share an unaccompanied minor’s background, starting a club focused on celebrating their culture can be especially meaningful. Encouraging students to participate in community and cultural groups both in and out of school will help them form connections.

It is valuable for students and their families to feel connected to their school in addition to their peers and community. Thorough family engagement can help with this. Family engagement works best when it’s linguistically and culturally sensitive and conducted through a cultural broker, someone who is part of the student’s cultural community and can speak to students and families on their terms. Ensuring students and families have access to translated materials, which they’re legally entitled to, is also vital to breaking through isolation. Schools should have interpreters or translation programs available to communicate with students and their caregivers. A fuller review of the rights of multilingual families is available here.

Eileen Kugler shares how schools can support immigrant families.

Resources

- For more resources on trauma-informed teaching, explore our curated resources on Immigrant Trauma and Mental Health.

- The four core stressors model is the basis for a toolkit that allows teachers to evaluate their students’ needs and challenges.

- This resource provides a comprehensive accounting of unaccompanied immigrant minor students’ educational legal rights. This resource shares the rights of English language learner families.

- This video from our Immigrant Student Success online workshop features social worker Laura Gardner sharing more information about unaccompanied immigrant minors and strategies for supporting them. Gardner also wrote a blog post, 10 Things Educators Need to Know about Unaccompanied Minors, summarizing many of her findings.

- Watch The ILC’s Pandemic, Politics and the Future: Tackling Immigrant Anxiety and Trauma webinar to learn more about addressing anxiety and trauma in the immigrant context.

- The Anti-Defamation League’s Kira Simon discusses resources for fighting anti-immigrant discrimination in the classroom. Teaching Tolerance’s Julie Bradley and Amy Melik discuss how to tackle bias in schools.