Immigrants are immense assets to the United States health care system. On the whole, foreign-born residents create a net benefit to the United States by paying more into the system than they receive in government-funded medical benefits. As workers, they fill crucial roles at every level of the health care system, from badly needed home health aides to surgeons and researchers. Their work has been particularly vital throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. With more inclusive policies around health care access, visas and licensing, immigrants could offer even more to the U.S. health care system.

Immigrant medical workers fill crucial gaps

Immigrants play an outsized role at every level of the United States health care system. Immigrants make up 13.6 percent of the U.S. population, but 28.0 percent of the country’s 958,000 physicians and surgeons, and 37.9 percent of the 492,000 home health aides. The latter group is especially key for meeting the needs of the United States’ rapidly aging population. Geriatric care is one of many areas where the U.S. health care system is facing worker shortages. Immigrant workers are especially likely to serve where the need is greatest, filling a disproportionate number of jobs where shortages are especially acute. Without immigrant workers, these gaps in care in underserved and rural areas would be far worse.

Immigrant workers have been particularly vital during the COVID-19 crisis. The huge role they play in the home health aide industry has kept many disabled and elderly people out of institutional care facilities, which have been hit very hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. They also make up one in eight respiratory therapists, one in 20 emergency technicians and more than half of geriatric medicine specialists. Immigrant contact tracers have helped track the spread of the virus among vulnerable populations, using multilingual and multicultural communication to obtain data that might otherwise have been lost.

Immigrants have also been crucial to the development of COVID-19 vaccines. The history of these vaccines can be told through the stories of immigrants in health care. Katalin Kariko, a Hungarian immigrant who pioneered mRNA science, struggled for funding and respect for years before making a breakthrough crucial to the development of the vaccine. Derek Rossi, a Canadian-born immigrant scientist and entrepreneur, saw the commercial potential of Kariko’s breakthrough and built on it, ultimately cofounding biotech company Moderna (“Modifying-RNA”). Noubar Afeyan, an Lebanese-born immigrant entrepreneur and investor, was Moderna’s first investor and champion. Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, married immigrant scientists and founders of BioNTech, also developed new innovations based on Kariko’s work. When COVID-19 first appeared, BioNTech reached out to Pfizer, a health care company that was itself founded by German-born immigrant entrepreneur Charles Pfizer, and partnered with them in developing a vaccine. Moderna and the BioNTech-Pfizer partnership were the first two organizations to get COVID-19 vaccines approved. This chain of events would not have occurred without the work of immigrants at every link.

Immigrant entrepreneur Jose de la Rosa describes how his home health care business has expanded the number of people who can access at-home care.

The ILC Public Education Institute’s webinar Immigrants in Health Care uses research and data to explore the work of foreign-born medical workers.

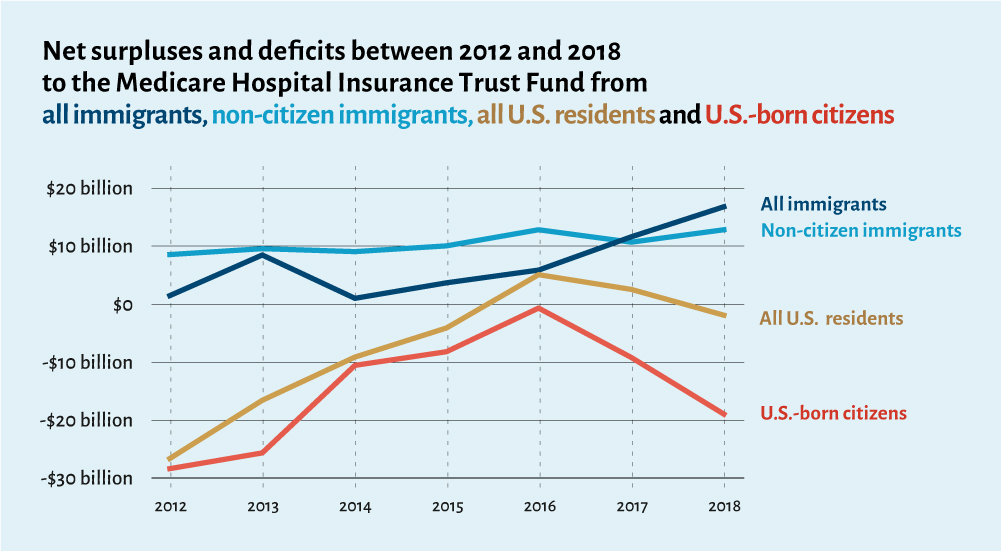

Immigrants’ contributions fund government health care

Immigrants pay more into government health care programs than they use in benefits, creating a net surplus. For example, immigrants paid $51 billion more in taxes that pay for Medicare than they used in Medicare-paid services between 2012 and 2018. The Medicare program has been famously running a deficit for some time and is predicted to become insolvent by 2026. So, how is it that immigrants are creating a surplus? Medicare is funded primarily through a payroll tax that applies to all U.S. workers regardless of immigration status, including more than half of undocumented immigrants. The program is used by eligible U.S. residents who are 65 or older. On average, immigrants are younger, healthier and more likely to be in the workforce than the U.S. born, and many are simply ineligible for government benefits.

Immigrating is hard. Most immigrants choose to come to the U.S. when they are relatively young and healthy and looking for work. That’s why immigrants are more likely to be working age and make up an outsized portion of the workforce. Seventy-six percent of immigrants and 63 percent of U.S. born are “working age” (15 to 64), and while the foreign-born make up 13.6 percent of the U.S. population, they represent 17.4 percent of the workforce.

According to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health, immigrants use fewer medical services across the board, reporting “fewer medical visits, inpatient admissions, outpatient hospital visits and emergency medical visits.” The disparity is even more pronounced among undocumented immigrants. Researchers at Tufts School of Medicine and Harvard Medical School found that undocumented immigrants account for just 1.4 percent of health care spending in the U.S. despite making up five percent of the total population.

When migrants do need to seek health care, they have limited access to government-funded programs. Only U.S. citizens and permanent legal residents (green card holders) are eligible for Medicare, meaning many more pay into the system than benefit from it. Non-citizen immigrants have limited access to programs like Medicaid, and most undocumented immigrants can’t get federal health care at all, including Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces, although some states fund access to these services. Refugees also have limited access to Medicaid and ACA marketplaces. In addition, policies like the public charge rule take rights away from immigrants who use or are predicted to use government benefits. While the public charge rule currently does not include health care benefits, uncertainty around the policy has still had a “chilling effect” that has decreased immigrants’ participation even in the programs that are available to them.

The combination of immigrants’ high tax contributions, fewer medical needs and limited access to government health care creates a surplus that benefits all Americans.

Building on the success of immigrants and health care

Immigrants could contribute even more to the U.S. health care system if they weren’t held back by outdated policies regarding health care access, immigration and licensing requirements. As noted above, immigrants have limited access to health care, particularly government-funded health care. This reduces costs in the short term, but lack of access to preventative care increases long term health care costs. For example, one study found that prenatal care can cut medical costs in half over time, but immigrant parents are less likely to receive this vital form of health care.

Research indicates that expanding immigrants’ access to health care, as well as clarifying and codifying the public charge rule so immigrants don’t fear using the benefits they are entitled to, could ultimately save all Americans significant amounts of money. Research also indicates that increasing access to health care is not a pull factor and does not lead to increases in immigration. Improving health care access is not likely to increase in-migration, but it would improve contact tracing, a vital tool for fighting the COVID-19 crisis that has been hampered by some immigrants’ fear of engaging with the health care system.

Visa and licensing requirements often hinder immigrants’ abilities to fully contribute to the United States’ health care system. There are programs and policies that help foreign-born health care workers overcome these obstacles that could be expanded to improve outcomes for all Americans in the future. For example, the Conrad 30 waiver program allows foreign-born medical students on J-1 visas to bypass the requirement that they return to their country of origin for two years if they agree to serve in rural and underserved communities. It’s a true win-win for foreign-born and U.S.-born Americans that is currently only available to 30 medical professionals per state.

During the COVID-19 crisis, multiple states loosened visa restrictions and licensing requirements to allow immigrant medical workers to serve in the places and positions where they were most needed. In doing so, the states eased some of the health care worker shortages and reduced “brain waste,” which occurs when foreign-trained medical workers cannot work in their field because of the struggle to get their credentials recognized in the United States. With more initiatives like these, the already impressive contributions of foreign-born Americans could expand.

In 2021, The ILC honored immigrant heroes of the COVID-19 crisis. This short video shares the story of Niall Lennon, whose work in biotechnology has helped more than 15 million people get tested for COVID-19.

Immigrants and health care, moving forward

Immigrants have a tremendous positive impact on the American health care system. With some small, specific changes, their impact could be even greater. Their already net-positive contribution to the health care system would likely increase if their access to health care also increased. The worker shortages they’re already alleviating could be even better filled by allowing more immigrants to make full use of their skills. Making licensing more accessible would help immigrants serve where they are most needed. All Americans would benefit from embracing the foreign-born residents who already do so much for the United States health care system.

Learn more

- Immigrant workers’ contributions to health care during the COVID-19 crisis are further detailed in The Immigrant Learning Center (The ILC) Public Education Institute’s research report Immigrant Essential Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

- The ILC’s research report Immigrants in Health Care: Keeping Americans Healthy Through Care and Innovation explores the many contributions of immigrant medical workers to the United States in more depth.

- The ILC’s Immigrant Entrepreneur Hall of Fame features many foreign-born founders who have innovated in health care, including Michael J. Fox, Charles Weissman, Ivor Royston, Ellen Browning Scripps, Kiran Patel and José Navarro, Sr.

- Many of The ILC’s English students work in or go on to work in health care. You can learn one of their stories in this short video.