The relationship between Black Americans and migration is complicated. For many African Americans, the idea of an immigrant heritage can be a painful reminder that their heritage was erased when their ancestors were enslaved and brought to this country. More recent Black migrants may know and be proud of their heritage, but the United States’ legacy of slavery means they face challenges that non-Black immigrants do not. Their immigrant status means they also face challenges that U.S.-born Black Americans do not. Ultimately, like all immigrant groups, Black immigrants from around the world find both challenges and opportunities for themselves and contribute to a stronger United States.

I came here as a refugee but not as a white refugee. My permanent home is the U.S. and my permanent color is Black.

The Invisible Intersection

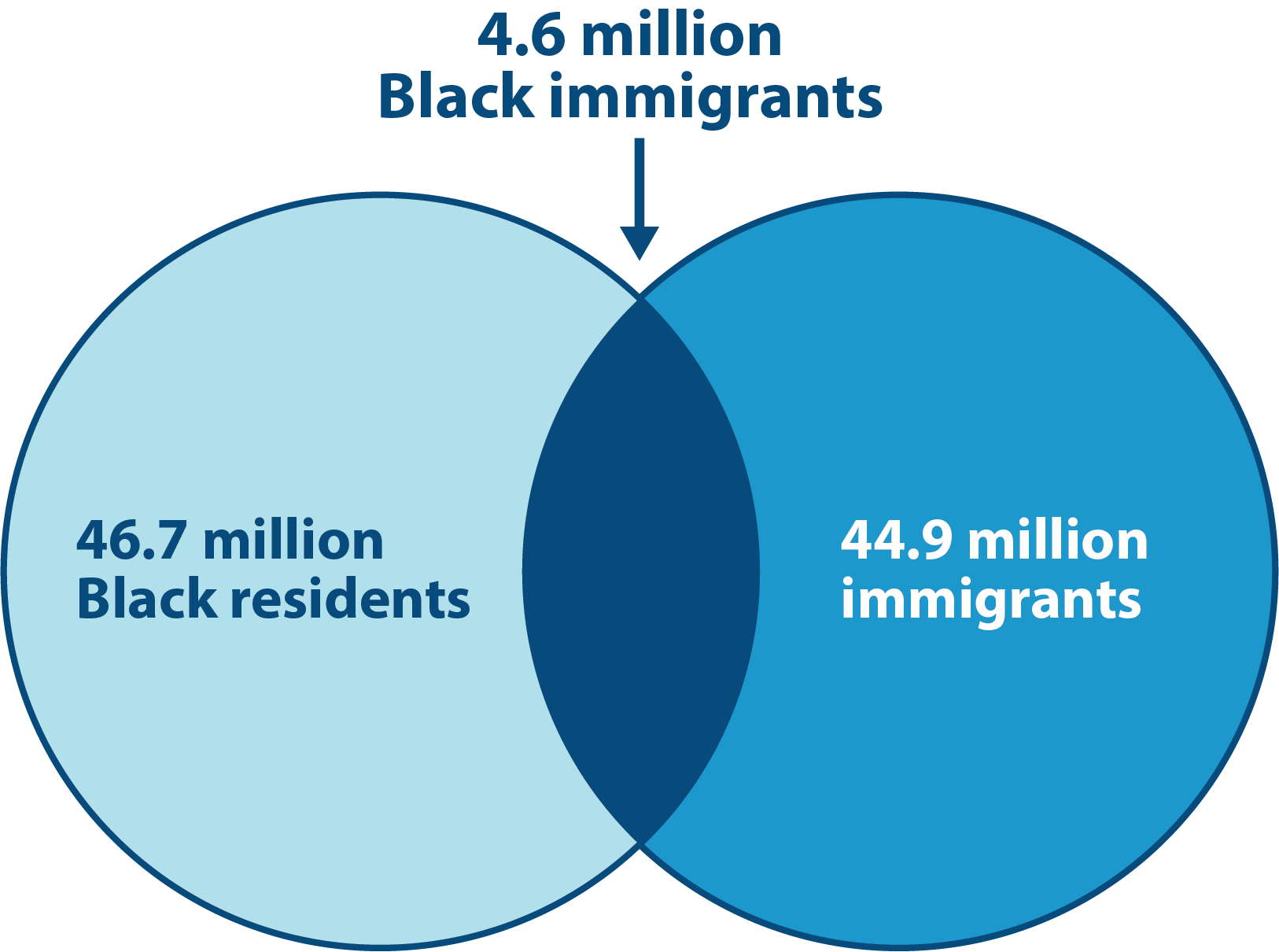

In 1970, one in 100 Black Americans was an immigrant. Today, they are one in 10.

Another one in ten are children of immigrants. This increase in immigration rates is likely to continue. Pew Research Center projects that the Black immigrant population in the U.S. will nearly double by 2060. Regional concentrations include refugees from Somali and Sudan in Minnesota, Ohio, Washington, Maine, etc., and “Little Haiti” enclaves in Miami, Brooklyn, Atlanta and other cities. Yet Black immigrants seem to be missing from the public consciousness. “Black” and “immigrant” are seen as separate identities. The public discussion of immigration in the United States focuses almost entirely on Latinx immigration, overlooking the 4.6 million Black immigrants currently in the country and ignoring the existence of Black, Latinx immigrants all together. Given this invisible intersection, how do Black immigrants connect to the wider community?

Black vs & Immigrant

The longstanding racial inequities in the United States combined with a history of blaming immigrants for so many societal problems have too often led to Black American and immigrant American communities being pitted against each other. Although there is little evidence to support it, some Black Americans have been led to believe that immigrants are to blame for Black communities’ economic struggles. On the other hand, the discrimination and marginalization that U.S.-born Black communities face can lead some Black immigrants to hold U.S.-born Black communities at arm’s length. In an interview with the Minnesota Digital Library, Somalian refugee Mohamed Jama describes being “warned against mixing with [B]lack Americans,” and first-generation Caribbean immigrant and professor Pedro Noguera writes in an essay that his parents “wanted to be distinguished from [B]lack Americans” to the point of telling him he wasn’t Black.

In reality, Black, immigrant and Black-immigrant communities have significant shared interests and a long history of collaboration. Many immigrants are aware of and respect the long struggle for civil rights in the Black community and how it relates to their own struggles.

I wouldn’t be able to be at this institution today without the work of African Americans who have laid the foundations for me.

In our webinar “Building United Communities of Immigrants and African Americans,” four experts discussed tools for building collaboration and solidarity in Black and immigrant communities:

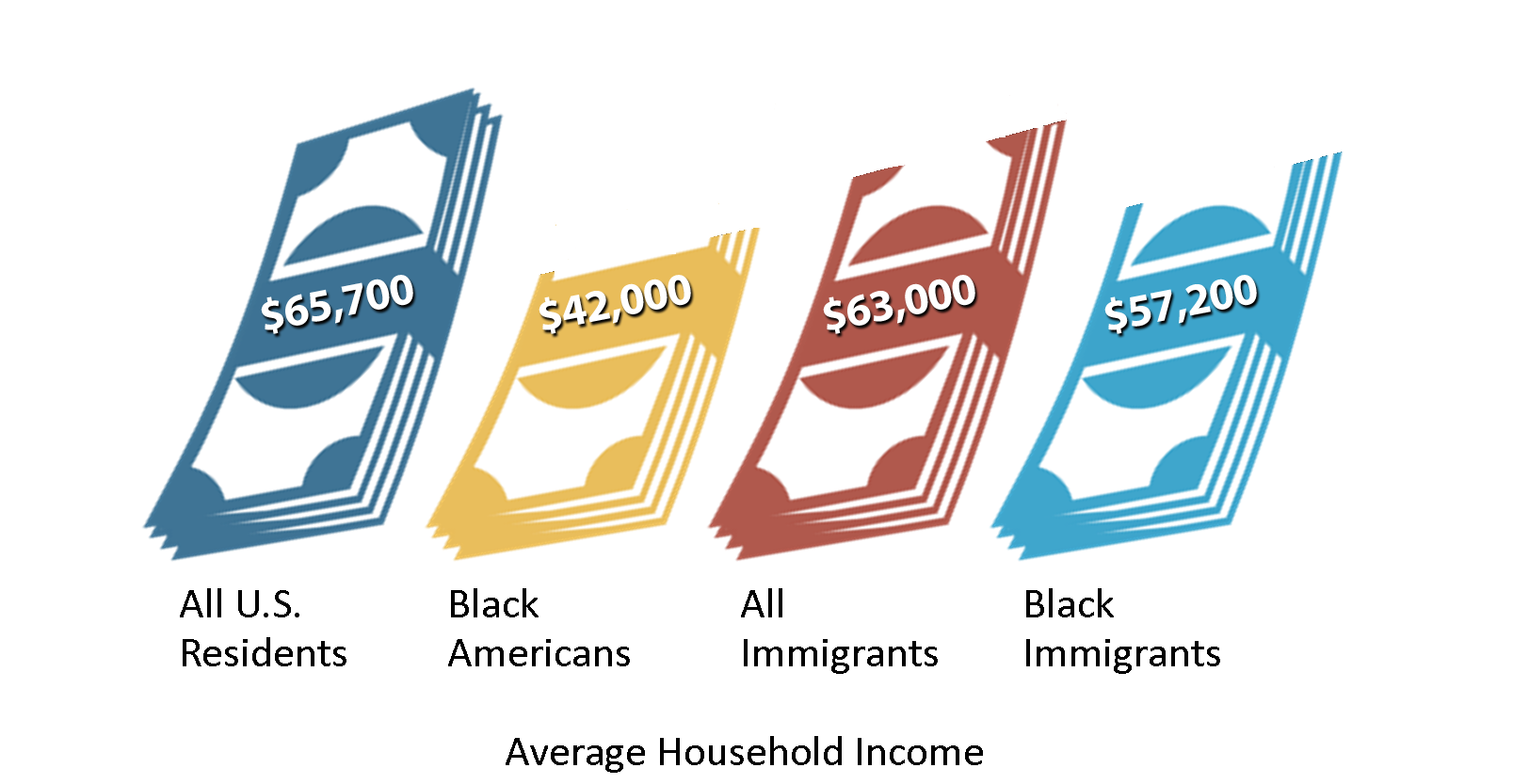

Economic Disadvantage

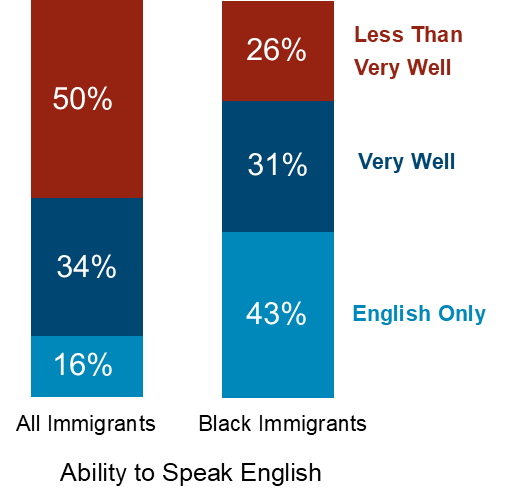

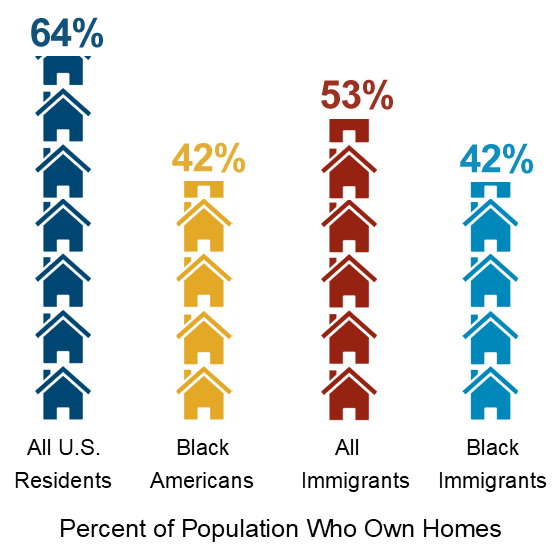

Common sense says that economic success is tied to the ability to speak English in the United States. There is plenty of research to back that up. The better a person’s English ability, the more likely they are to be employed and the higher their income. Why is it that Black immigrants have far better English skills on average yet much lower income than other immigrants? Black immigrant households make $8,500 less than the average U.S. household and $5,800 less than the average immigrant household. They are also more likely to live under the federal poverty line, be unemployed and have trouble paying for things like food and health care.

Black Immigrants Have Lower Average Income Than All U.S. Residents and All Other Immigrants

Source: Pew Research Center

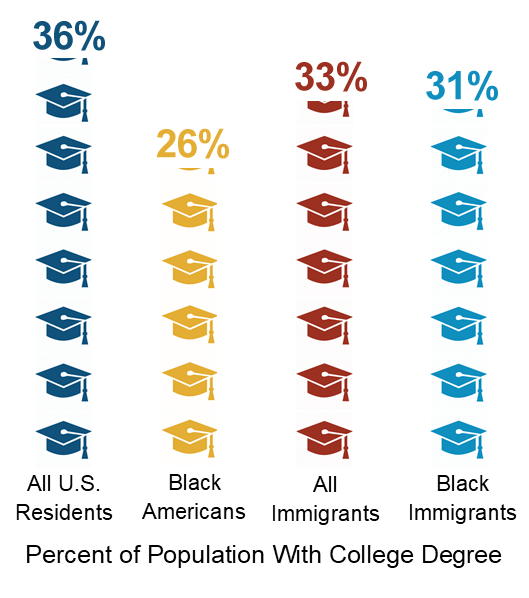

The answer does not lie in education. Black immigrants have similar levels of education as all immigrants on average, and sub-Saharan African immigrants are the best educated of any immigrant group. A partial explanation is that highly-educated immigrants can have difficulty finding work in their field because of barriers to transferring skills and accreditation from their home country. Given that Black people in the United States make less money on average than white people, even while working the same jobs at the same skill level, a more complete answer involves taking a look at the role of racial as well as anti-immigrant bias. As an example, one survey reports that more than half of employed black immigrants reported discrimination at work.

Despite these disadvantages, Black immigrants make significant contributions to the United States economy. In 2021, Black immigrant households earned $153 billion in income, paying $24 billion in federal income taxes and $15 billion in state and local taxes. Black immigrant entrepreneurs from singer and beauty mogul Robyn Rihanna Fenty to cybersecurity expert Herby Duverne create jobs and strengthen the economy.

Becoming a Minority

Immigrants must often adjust to becoming an ethnic minority for the first time when they come to the United States. For many, it is the first time in their lives they face discrimination based simply on their features or skin color, and it can be traumatic. Most Black immigrants come from countries of origin in Africa or the Caribbean, where they are in the racial majority. This can be particularly noticeable in social settings such as school. Many Black immigrant students report struggling with becoming the “other” for the first time.

“The students, for example, who came from Haiti, they’re not Black in Haiti. They’re Haitian. Then, when you enroll in U.S. schools and you’re filling out those school enrollment forms, the question of race is there,” Dr. Ayanna Cooper, an educational consultant for culturally and linguistically diverse learners said in a talk for The Immigrant Learning Center. “So the idea that they have become Black now is a phenomenon that we have to wrap our heads around.”

Black immigrants arriving from majority-Black countries may find that U.S.-born Black Americans can help them navigate the new experience of being considered a “minority.” Relationships with U.S.-born Black people are especially helpful for Black immigrant students adapting to a new culture and school environment.

Some of my friends who were African American, they help[ed] me in that transition and that was really great.

Bias in Education

As a group, Black immigrants have a better than average knowledge of English, but four in 10 still need help learning the language. The disproportionate focus on Latinx immigrants in media creates a stereotype of English language learners that Black immigrants don’t match, which can make it harder for them to access the resources they need. As an example, an ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) teacher described in an interview with Colorín Colorado that another teacher thought her Black, English language learners were “in the wrong room.” These assumptions can be alienating to students who are often also facing racial discrimination for the first time.

As a group, Black immigrants have a better than average knowledge of English, but four in 10 still need help learning the language. The disproportionate focus on Latinx immigrants in media creates a stereotype of English language learners that Black immigrants don’t match, which can make it harder for them to access the resources they need. As an example, an ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) teacher described in an interview with Colorín Colorado that another teacher thought her Black, English language learners were “in the wrong room.” These assumptions can be alienating to students who are often also facing racial discrimination for the first time.

Research shows that teacher expectations can have a meaningful impact on student performance. Too often, implicit racial bias leads teachers to set lower expectations for Black students. The same is true for bias against students who are not native English speakers. Black immigrant students who don’t speak English well face a double bind of lowered expectations. Despite studies indicating that Black immigrant children are well-prepared for schooling at home, a report on Black immigrant students found that even high-achieving students were deemed to be “academically inferior” if they were also English language learners. This can translate into measurable differences.

A report from the U.S. Department of Education shows that Black, English language learners (ELLs) perform worse on reading and math exams than either non-Black ELLs or Black native speakers. Bias in schools can have even more serious consequences. Black students are more likely than non-Black students to be arrested for the same behaviors, which in turn funnels them into the criminal justice system.

Being around everybody that’s white, predominantly, and you’re the only person of some type of color in there … I’ve never really done it, so that’s one thing I’ll be kinda nervous about.

Bias in Criminal Justice

When the vulnerabilities of race and immigration status intersect, they form a “prison to deportation pipeline,” a term used to describe a system that works to funnel Black and Latinx immigrants from the criminal court system into Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) custody. Black immigrants are more likely to be detained, returned to their home country and prevented from returning than immigrants of other races or ethnicities. They are also less likely to have their application for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) accepted. This is not surprising when you consider the experience of Black, U.S.-born people in the United States. Black people are equally likely as other Americans to commit crimes, but they are significantly more likely to be stopped, questioned, arrested, charged, denied bail, convicted and serve longer sentences.

Immigrants are actually less likely than U.S.-born people to commit a crime, but immigrants of color are still more likely to become involved with the criminal justice system. Black and Latinx residents in the United States are more likely to be stopped by police than white residents, and when stopped, police are twice as likely to threaten or use force against them. St. Lucian American immigrant Botham Jean made national headlines after he was murdered by a white police officer who had broken into his apartment.

Although they both face increased undue attention from police, the stakes are higher for Black immigrants than those born here or non-Black immigrants. Black immigrants make up one in five non-citizens facing deportation on criminal grounds, which is close to three times their share of the non-citizen population. Even a minor criminal charge can derail an immigration process or end in deportation. In fact, offenses that are treated as misdemeanors in criminal courts can be cause for automatic deportation in immigration court.

One in five non-citizens facing deportation is Black.

Making Meaning

Although much needs to be done to level the playing field, each person must ultimately decide for themselves what it means to be Black and an immigrant in the United States. Like all immigrants, they come here with a fierce desire to improve their lives and their new homeland, and Black immigrants find ways to make a home for themselves here. Black history is full of stories of great achievement, including luminaries like Claude McKay, Kwame Ture and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. In 2021, Black immigrants contributed $39 billion in tax revenue annually. They’re more likely to complete master’s, professional, or doctorate-level programs and are more likely to start businesses than U.S.-born Americans, creating more jobs for everyone. With some help, they can be even more successful. Here are a few ideas for public servants, teachers, not-for-profits, community organizers and anyone whose work intersects with immigrants.

Get data:

Understand who is in your community and find out what they need. More than just foreign-born or not, try to discover the racial, ethnic, nationality, gender, etc. makeup of your community. Are there immigrants from Nigeria, Haiti or Zambia, for example? How are their needs different from immigrants from other countries, or Black or white U.S.-born citizens? A great source for such data is Immigration Data on Demand, a free service from the Institute for Immigration Research at George Mason University. There are several pre-existing fact sheets available, and you can request a custom fact sheet including the geography and demographic information that’s relevant to you.

Get trained:

There is a wealth of resources to help educators teaching immigrant students and address implicit bias in schools. The Immigrant Learning Center has around a decade‘s worth of recordings and resources from our free, online Resource Hub.

For example, speakers during the 2022 Immigrant Success Conference discussed strategies for supporting immigrant students in the classroom. School Social Worker Alaísa Grudzinski specifically addressed the issues with the so-called “color blind” approach to racism and how educators can avoid erasing the experiences of students of color.

“Know Your Rights” trainings can help Black immigrants navigate encounters with the police, decreasing the likelihood that they will be sucked into a criminal justice system that could endanger their immigration status.

Joseph Ngaruiya, winner of The ILC’s Immigrant Entrepreneur Business Growth Award in 2019, immigrated to America from Kenya as a child. He brought with him a traditional Kenyan reverence for elders and their wisdom, which motivated him to start his homecare business, A Better Life Homecare. Joseph is passionate about providing elderly and disabled people with dignified, in-home care, regardless of income level.

Get together:

Immigrant–serving organizations must form stronger coalitions with racial justice organizations, recognizing the shared goals and needs of the two movements. The history of coalition building between immigrant and racial justice organizations shows that such cooperation is not only possible but powerful.

In The Immigrant Learning Center’s conference on uniting immigration with other social causes, Dr. Kim Tabari of the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration at the University of Southern California presented on the intersection of race and immigration. The video is cued to start when she offers six strategies for collaborative action:

- The Black Alliance for Just Immigration provides a wealth of information and resources for people seeking to learn and do more on this issue.

- Organizations like the Black Immigrant Collective and the UndocuBlack Network offer more resources to support Black immigrants.

- Learn more about extraordinary Black immigrants throughout U.S. history in our article, Black History Month: 10 Famous Black Immigrants.

- The book Immigrant Struggles, Immigrant Gifts is composed of 11 essays on 11 immigrant groups. Chapter Nine offers an in-depth discussion of the history of Black West Indian immigration.

- The Education Week article Assumptions Teachers Often Make About Black Students and What to Do About Them describes common stereotypes of Black immigrant students and strategies for tackling them.

- The Immigration Initiative at Harvard University offers a fact sheet and checklist for ways to support Black immigrant students and their families.

- Research shows that the media people consume can shape their worldview. These collections of books and film and TV shows include many representations of Black immigrants that can widen perspectives.

Updated April 2025